Blog

2018-05-02

Every morning just before 7am, one of the Today Programme's presenters reads out a puzzle. Yesterday, it was this puzzle:

In a given month, the probability of a certain daily paper either running a story about inappropriate behaviour at a party conference or running one about somebody's pet being retrieved from a domestic appliance is exactly half the probability of the same paper containing a photo of a Tory MP jogging. The probability of no such photo appearing is the same as that of there being a story about inappropriate behaviour at a party conference. The probability of the paper running a story about somebody's pet being retrieved from a domestic appliance is a quarter that of its containing a photo of a Tory MP jogging. What are the probabilities the paper will (a) run the conference story, (b) run the pet story, (c) contain the jogging photo?

I'm not the only one to notice that some of Radio 4's daily puzzles are not great.

I think this puzzle is a great example of a terrible puzzle. You can already see the first problem with it: it's long and words and very hard to follow on the radio.

But maybe this isn't so important, as you can

read it here after it's been read out.

Once you've done this, you can re-write the puzzle as follows:

there are three news stories (\(A\), \(B\) and \(C\)) that the newspaper might publish in a month. We are given the following information:

$$\mathbb{P}(A\text{ or }B)=\tfrac12\mathbb{P}(C)$$

$$1-\mathbb{P}(C)=\mathbb{P}(A)$$

$$\mathbb{P}(B)=\tfrac14\mathbb{P}(C)$$

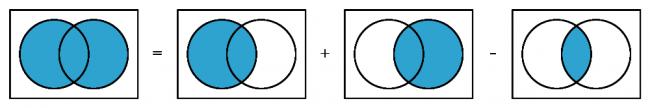

To solve this puzzle, we need use the formula \(\mathbb{P}(A\text{ or }B)=\mathbb{P}(A)+\mathbb{P}(B)-\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)\).

These Venn diagrams justify this formula:

Venn diagrams showing that \(\mathbb{P}(A\text{ or }B)=\mathbb{P}(A)+\mathbb{P}(B)-\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)\).

Using the information we were given in the question, we get:

\begin{align}

\tfrac12\mathbb{P}(C)&=\mathbb{P}(A\text{ or }B)\\

&=1-\mathbb{P}(C)+\tfrac14\mathbb{P}(C)-\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)\\

\mathbb{P}(C)&=\tfrac45(1-\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)).

\end{align}

At this point we have reached the second problem with this puzzle: there's no answer unless we make some extra assumptions, and the question doesn't make it clear what we can assume.

But let's give the puzzle the benefit of the doubt and try some assumptions.

Assumption 1: The events are mutually exclusive

If we assume that the events \(A\) and \(B\) are mutually exclusive—or, in other words, only one of these two articles can be published,

perhaps due to a lack of space—then we can use the fact that

$$\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)=0.$$

This means that

\(\mathbb{P}(C)=\tfrac45\),

\(\mathbb{P}(A)=\tfrac15\), and

\(\mathbb{P}(B)=\tfrac15\). There's a problem with this answer, though: the three probabilities add up to more than 1.

This wouldn't be a problem, except we assumed that only one of the articles \(A\) and \(B\) could be published.

The probabilities adding up to more than 1 means that either \(A\) and \(C\) are not mutually exclusive or \(A\) and \(B\) are not mutually exclusive,

so \(C\) could be published alongside \(A\) or \(B\). There seems to be nothing special about the three news stories to mean that only some combinations

could be published together, so at this point I figured that this assumption was wrong and moved on.

Today, however, the answer was posted, and

this answer was given (without an working out). So we have a third problem with this puzzle: the answer that was given is wrong, or at the very best

is based on questionable assumptions.

Assumption 2: The events are independent

If we assume that the events are independent—so one article being published doesn't affect whether or not another is published—then

we may use the fact that

$$\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)=\mathbb{P}(A)\mathbb{P}(B).$$

If we let \(c=\mathbb{P}(C)\), then we get:

\begin{align}

\tfrac12c&=\mathbb{P}(A)+\mathbb{P}(B)-\mathbb{P}(A\text{ and }B)\\

&=\mathbb{P}(A)+\mathbb{P}(B)-\mathbb{P}(A)\mathbb{P}(B)\\

&=1-c+\tfrac14c-\tfrac14(1-c)c\\

\tfrac14c^2-\tfrac32c+1&=0.

\end{align}

You can use your favourite formula to solve this to find that \(c=3-\sqrt5\), and therefore

\(\mathbb{P}(A)=\sqrt5-2\) and

\(\mathbb{P}(B)=\tfrac34-\tfrac{\sqrt5}4\).

In this case, our assumption appears to be more reasonable—as over the course of a month the stories published by a paper probably don't have

much of an effect on each other—but we have the fourth, and probably biggest problem with the puzzle: the question and answer are not interesting or surprising, and

the method is a bit tedious.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

2018-05-03

@Stefan: It's possible that that was intended but it's not completely clear. If that was the intention, I stick to my point that it's odd that the other story can be published alongside these two.Matthew

Doesn’t the word ‘either’ in the opening phrase make A and B explicity exclusive?

Stefan

Add a Comment