Blog

2019-04-09

In the latest issue of Chalkdust,

I wrote an article

with Edmund Harriss about the Harriss spiral that appears on the cover of the magazine.

To draw a Harriss spiral, start with a rectangle whose side lengths are in the plastic ratio; that is the ratio \(1:\rho\)

where \(\rho\) is the real solution of the equation \(x^3=x+1\), approximately 1.3247179.

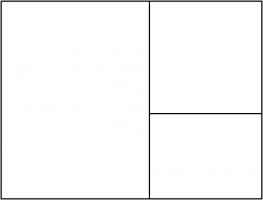

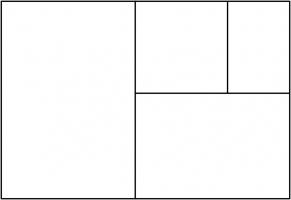

This rectangle can be split into a square and two rectangles similar to the original rectangle. These smaller rectangles can then be split up in the same manner.

Drawing two curves in each square gives the Harriss spiral.

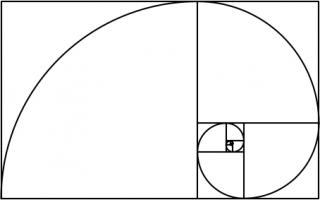

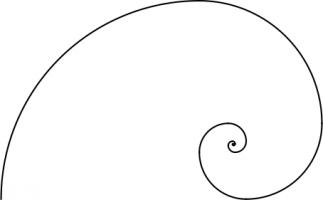

This spiral was inspired by the golden spiral, which is drawn in a rectangle whose side lengths are in the golden ratio of \(1:\phi\),

where \(\phi\) is the positive solution of the equation \(x^2=x+1\) (approximately 1.6180339). This rectangle can be split into a square and one

similar rectangle. Drawing one arc in each square gives a golden spiral.

The golden and Harriss spirals are both drawn in rectangles that can be split into a square and one or two similar rectangles.

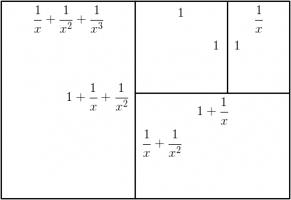

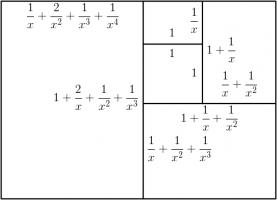

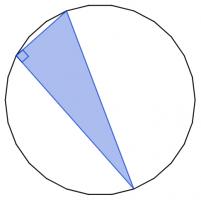

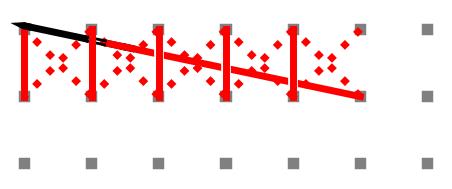

Continuing the pattern of these arrangements suggests the following rectangle, split into a square and three similar rectangles:

Let the side of the square be 1 unit, and let each rectangle have sides in the ratio \(1:x\). We can then calculate that the lengths of

the sides of each rectangle are as shown in the following diagram.

The side lengths of the large rectangle are \(\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1\) and \(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\). We want these to also

be in the ratio \(1:x\). Therefore the following equation must hold:

$$\frac{1}{x^3}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac2x+1=x\left(\frac1{x^2}+\frac1x+1\right)$$

Rearranging this gives:

$$x^4-x^2-x-1=0$$

$$(x+1)(x^3-x^2-1)=0$$

This has one positive real solution:

$$x=\frac13\left(

1

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29-3\sqrt{93})}

+\sqrt[3]{\tfrac12(29+3\sqrt{93})}

\right).$$

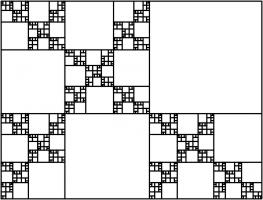

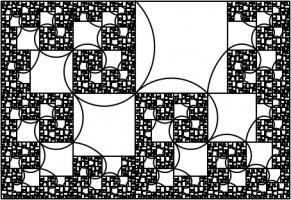

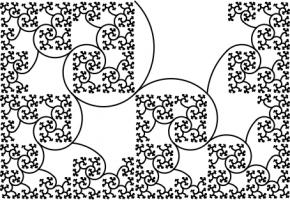

This is equal to 1.4655712... Drawing three arcs in each square allows us to make a spiral from a rectangle with sides in this ratio:

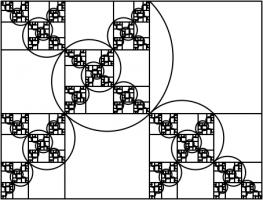

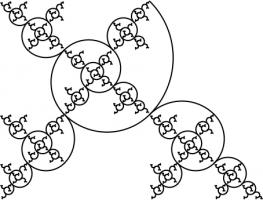

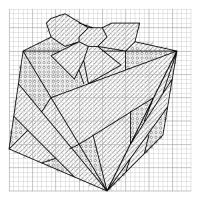

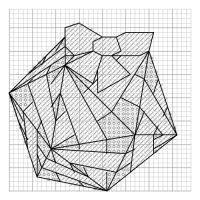

Adding a fourth rectangle leads to the following rectangle.

The side lengths of the largest rectangle are \(1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4}\) and \(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\).

Looking for the largest rectangle to also be in the ratio \(1:x\) leads to the equation:

$$1+\frac2x+\frac3{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}+\frac1{x^4} = x\left(1+\frac2x+\frac1{x^2}+\frac1{x^3}\right)$$

$$x^5+x^4-x^3-2x^2-x-1 = 0$$

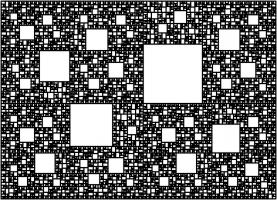

This has one real solution, 1.3910491... Although for this rectangle, it's not obvious which arcs to draw to make a

spiral (or maybe not possible to do it at all). But at least you get a pretty fractal:

We could, of course, continue the pattern by repeatedly adding more rectangles. If we do this, we get the following polynomials

and solutions:

| Number of rectangles | Polynomial | Solution |

| 1 | \(x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.618033988749895 |

| 2 | \(x^3 - x - 1=0\) | 1.324717957244746 |

| 3 | \(x^4 - x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.465571231876768 |

| 4 | \(x^5 + x^4 - x^3 - 2x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.391049107172349 |

| 5 | \(x^6 + x^5 - 2x^3 - 3x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.426608021669601 |

| 6 | \(x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^4 - 3x^3 - 4x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4082770325090774 |

| 7 | \(x^8 + 2x^7 + 2x^6 - 2x^5 - 5x^4 - 4x^3 - 5x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.4172584399350432 |

| 8 | \(x^9 + 3x^8 + 2x^7 - 5x^5 - 9x^4 - 5x^3 - 6x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.412713760332943 |

| 9 | \(x^{10} + 3x^9 + 5x^8 - 5x^6 - 9x^5 - 14x^4 - 6x^3 - 7x^2 - x - 1=0\) | 1.414969877544769 |

The numbers in this table appear to be heading towards around 1.414, or \(\sqrt2\).

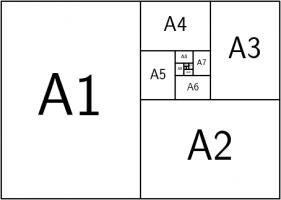

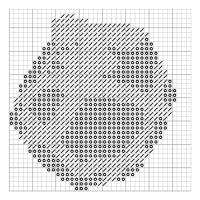

This shouldn't come as too much of a surprise because \(1:\sqrt2\) is the ratio of the sides of A\(n\) paper (for \(n=0,1,2,...\)).

A0 paper can be split up like this:

This is a way of splitting up a \(1:\sqrt{2}\) rectangle into an infinite number of similar rectangles, arranged following the pattern,

so it makes sense that the ratios converge to this.

Other patterns

In this post, we've only looked at splitting up rectangles into squares and similar rectangles following a particular pattern. Thinking about

other arrangements leads to the following question:

Given two real numbers \(a\) and \(b\), when is it possible to split an \(a:b\) rectangle into squares and \(a:b\) rectangles?

If I get anywhere with this question, I'll post it here. Feel free to post your ideas in the comments below.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

2019-05-02

@g0mrb: CORRECTION: There seems to be no way to correct the glaring error in that comment. A senior moment enabled me to reverse the nomenclature for paper sizes. Please read the suffixes as (n+1), (n+2), etc.(anonymous)

I shall remain happy in the knowledge that you have shown graphically how an A(n) sheet, which is 2 x A(n-1) rectangles, is also equal to the infinite series : A(n-1) + A(n-2) + A(n-3) + A(n-4) + ... Thank-you, and best wishes for your search for the answer to your question.

g0mrb

Add a Comment

2019-03-26

I originally wrote this post for The Aperiodical.

A few months ago, Adam Townsend went to lunch and had a conversation. I wasn't there, but I imagine the conversation went something like this:

Adam: Hello.Smitha: Hello.Adam: How are you?Smitha: Not bad. I've had a funny idea, actually.Adam: Yes?Smitha: You know how the \hat command in LaTeΧ puts a caret above a letter?... Well I was thinking it would be funny if someone made a package that made the \hat command put a picture of an actual hat on the symbol instead?Adam: (After a few hours of laughter.) I'll see what my flatmate is up to this weekend...Jeff: What on Earth are you two talking about?!

As anyone who has been anywhere near maths at a university in the last ∞ years will be able to tell you,

LaTeΧ is a piece of maths typesetting software. It's a bit like a version of Word that runs in terminal and makes PDFs with really

pretty equations.

By default, LaTeΧ can't do very much, but features can easily added by importing packages: importing the graphicsx

package allows you to put images in your PDF; importing geometry allows you to easily change the page margins; and importing

realhats makes the \hat command put real hats above symbols.

Changing the behaviour of \hat

By default, the LaTeΧ command \hat puts a pointy "hat" above a symbol:

After Adam's conversation, we had a go at redefining the \hat command by putting the following

at the top of our LaTeΧ file.

LaTeΧ

\renewcommand{\hat}[1]{% We put our new definition here

}

After a fair amount of fiddling with the code, we eventually got it to produce the following result:

We were now ready to put our code into a package so others could use it.

How to write a package

A LaTeΧ package is made up of:

- a sty file, containing a collection of commands like the one we wrote above;

- a PDF of documentation showing users how to use your package;

- a README file with a basic description of your package.

It's quite common to make the first two of these by making a

dtx file

and an ins file. And no, we have

no idea either why these are the file extensions used or why this is supposedly simpler than making a sty file and a PDF.

The ins file says which bits of the dtx should be used to make up the sty file.

Our ins file looks like this:

LaTeΧ

\input{docstrip.tex}\keepsilent

\usedir{tex/latex/realhats}

\preamble

*License goes here*

\endpreamble

\askforoverwritefalse

\generate{

\file{realhats.sty}{\from{realhats.dtx}{realhats}}

}

\endbatchfile

The most important command in this file is \generate: this says that that the file

realhats.sty should be made from the file realhats.dtx

taking all the lines that are marked as part of realhats. The following is part of our dtx file:

LaTeΧ

%\lstinline{realhats} is a package for \LaTeX{} that makes the \lstinline{\hat}%command put real hats on symbols.

%For example, the input \lstinline@\hat{a}=\hat{b}@ will produce the output:

%\[\hat{a}=\hat{b}\]

%To make a vector with a hat, the input \lstinline@\hat{\mathbf{a}}@ produces:

%\[\hat{\mathbf{a}}\]

%

%\iffalse

%<*documentation>

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{realhats}

\usepackage{doc}

\usepackage{listings}

\title{realhats}

\author{Matthew W.~Scroggs \& Adam K.~Townsend}

\begin{document}

\maketitle

\DocInput{realhats.dtx}

\end{document}

%</documentation>

%\fi

%\iffalse

%<*realhats>

\NeedsTeXFormat{LaTeX2e}

\ProvidesPackage{realhats}[2019/02/02 realhats]

\RequirePackage{amsmath}

\RequirePackage{graphicx}

\RequirePackage{ifthen}

\renewcommand{\hat}[1]{

% We put our new definition here

}

%</realhats>

%\fi

The lines near the end between <*realhats>

and </realhats> will be included in the sty file, as they are marked at part of

realhats.

The rest of this file will make the PDF documentation when the dtx file is compiled.

The command \DocInput tells LaTeΧ to include the dtx again, but with the

%s that make lines into comments removed. In this way all the comments that describe the functionality will end up

in the PDF. The lines that define the package will not be included in the PDF as they are between \iffalse and

\fi.

Writing both the commands and the documentation in the same file like this means that the resulting file is quite a mess, and really quite

ugly. But this is apparently the standard way of writing LaTeΧ packages, so rest assured that it's not just our code that ugly and

confusing.

What to do with your package

Once you've written a package, you'll want to get it out there for other people to use. After all, what's the point of being able to

put real hats on top of symbols if the whole world can't do the same?

First, we put the source code of our package on GitHub, so that Adam and I had an

easy way to both work on the same code. This also allows other LaTeΧ lovers to see the source and contribute to it, although none have

chosen to add anything yet.

Next, we submitted our package to CTAN, the Comprehensive TeΧ Archive Network.

CTAN is an archive of thousands of LaTeΧ packages, and putting realhats there gives LaTeΧ users

everywhere easy access to real hats. Within days of being added to CTAN, realhats was added (with no work by us)

to MikTeX and TeX Live

to allow anyone using these LaTeΧ distributions to seemlessly install it as soon as it is needed.

We figured that the packaged needed a website too, so we made one. We also figured that the website

should look as horrid as possible.

How to use realhats

So if you want to end fake hats and put real hats on top of your symbols, you can simply write \usepackage{realhats}

at the top of your LaTeΧ file.

realhats: gotta put them all in academic papers

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

I am a pensioner studying maths with OU. Currently doing M248 stats module. My enjoyment of MLEs has been magnified by your wonderful realhats package. It's a good job I'm 99% tee-total or my tutor would be getting a dubious assignment (still leaves a 1% chance of malt-driven mischief though).

Dave

Add a Comment

2019-01-01

It's 2019, and the Advent calendar has disappeared, so it's time to reveal the answers and annouce the winners.

But first, some good news: with your help, Santa was able to work out who had stolen the presents and save Christmas:

Now that the competition is over, the questions and all the answers can be found here.

Before announcing the winners, I'm going to go through some of my favourite puzzles from the calendar, reveal the solution and a couple of notes and Easter eggs.

Highlights

My first highlight is the first puzzle in the calendar. This is one of my favourites as it has a pleasingly neat solution involving a

surprise appearance of a very famous sequence.

1 December

There are 5 ways to write 4 as the sum of 1s and 2s:

- 1+1+1+1

- 2+1+1

- 1+2+1

- 1+1+2

- 2+2

Today's number is the number of ways you can write 12 as the sum of 1s and 2s.

My next highlight is a puzzle that I was particularly proud of cooking up: again, this puzzle at first glance seems like it'll take a

lot of brute force to solve, but has a surprisingly neat solution.

10 December

The equation \(x^2+1512x+414720=0\) has two integer solutions.

Today's number is the number of (positive or negative) integers \(b\) such that \(x^2+bx+414720=0\) has two integer solutions.

My next highlight is a geometry problem that appears to be about polygons, but actually it's about a secret circle.

12 December

There are 2600 different ways to pick three vertices of a regular 26-sided shape. Sometimes the three vertices you pick form a right angled triangle.

Today's number is the number of different ways to pick three vertices of a regular 26-sided shape so that the three vertices make a right angled triangle.

My final highlight is a puzzle about the expansion of a fraction in different bases.

22 December

In base 2, 1/24 is

0.0000101010101010101010101010...

In base 3, 1/24 is

0.0010101010101010101010101010...

In base 4, 1/24 is

0.0022222222222222222222222222...

In base 5, 1/24 is

0.0101010101010101010101010101...

In base 6, 1/24 is

0.013.

Therefore base 6 is the lowest base in which 1/24 has a finite number of digits.

Today's number is the smallest base in which 1/10890 has a finite number of digits.

Note: 1/24 always represents 1 divided by twenty-four (ie the 24 is written in decimal).

Notes and Easter eggs

I had a lot of fun this year coming up with the names for the possible theives. In order to sensibly colour code each suspect's clues,

there is a name of a colour hidden within each name:

Fred Metcalfe,

Jo Ranger,

Bob Luey,

Meg Reeny, and

Kip Urples.

Fred Metcalfe's colour is contained entirely within his forename, so you may be wondering

where his surname came from. His surname is shared with Paul Metcalfe—the real name of a captain whose codename was a certain shade of red.

On 20 December, Elijah Kuhn emailed me to point out that it was possible to solve the final puzzle a few days early: although he could not yet work

out the full details of everyone's timetable, he had enough information to correctly work out who the culprit was and between which times the theft

had taken place.

Once you've entered 24 answers, the calendar checks these and tells you how many are correct. This year, I logged the answers that were sent

for checking and have looked at these to see which puzzles were the most and least commonly incorrect. The bar chart below shows the total number

of incorrect attempts at each question.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Day | |||||||||||||||||||||||

You can see that the most difficult puzzles were those on

13,

24, and

10 December;

and the easiest puzzles were on

5,

23,

11, and

15 December.

I also snuck a small Easter egg into the door arrangement: the doors were arranged to make a magic square, with each row and column, plus the two diagonals, adding to 55.

The solutions to all the individual puzzles can be found here. Using the clues, you can work out that everyone's seven activities

formed the following timetable.

| Bob Luey | Fred Metcalfe | Jo Ranger | Kip Urples | Meg Reeny |

| 0:00–1:21 Billiards | 0:00–2:52 Maths puzzles | 0:00–2:33 Maths puzzles | 0:00–1:21 Billiards | 0:00–1:10 Ice skating |

| 1:10–2:33 Skiing | ||||

| 1:21–2:52 Ice skating | 1:21–2:52 Stealing presents | |||

| 2:33–4:45 Billiards | 2:33–4:45 Billiards | |||

| 2:52–3:30 Lunch | 2:52–3:30 Lunch | 2:52–3:30 Lunch | ||

| 3:30–4:45 Climbing | 3:30–4:45 Climbing | 3:30–4:45 Climbing | ||

| 4:45–5:42 Curling | 4:45–5:42 Curling | 4:45–5:42 Curling | 4:45–5:42 Curling | 4:45–5:42 Lunch |

| 5:42–7:30 Maths puzzles | 5:42–7:30 Ice skating | 5:42–7:30 Chess | 5:42–7:30 Chess | 5:42–7:30 Maths puzzles |

| 7:30–10:00 Skiing | 7:30–9:45 Chess | 7:30–8:45 Skiing | 7:30–10:00 Maths puzzles | 7:30–9:45 Chess |

| 8:45–9:45 Lunch | ||||

| 9:45–10:00 Table tennis | 9:45–10:00 Table tennis | 9:45–10:00 Table tennis | ||

Following your investigation, Santa found all the presents hidden under Kip Urples's bed, fired Kip and sucessfully delivered all the presents

on Christmas Eve.

The winners

And finally (and maybe most importantly), on to the winners: 73 people submitted answers to the final logic puzzle. Their (very) approximate locations are shown on this map:

From the correct answers, the following 10 winners were selected:

| 1 | Sarah Brook |

| 2 | Mihai Zsisku |

| 3 | Bhavik Mehta |

| 4 | Peter Byrne |

| 5 | Martin Harris |

| 6 | Gert-Jan de Vries |

| 7 | Lyra |

| 8 | James O'Driscoll |

| 9 | Harry Poole |

| 10 | Albert Wood |

Congratulations! Your prizes will be on their way shortly. Additionally, well done to

Alan Buck, Alex Ayres, Alex Bolton, Alex Lam, Alexander Ignatenkov, Alexandra Seceleanu, Andrew Turner, Ashwin Agarwal,

Becky Russell, Ben Reiniger, Brennan Dolson,

Carl Westerlund, Cheng Wai Koo, Christopher Embrey, Corbin Groothuis,

Dan Whitman, David, David Ault, David Kendel, Dennis Oltmanns,

Elijah Kuhn, Eric, Eric Kolbusz, Evan Louis Robinson,

Felix Breton, Fred Verheul,

Gregory Loges,

Hannah,

Jean-Noël Monette, Jessica Marsh, Joe Gage, Jon Palin, Jonathan Winfield,

Kai Lam,

Louis de Mendonca,

M Oostrom, Martine Vijn Nome, Matt Hutton, Matthew S, Matthew Wales, Michael DeLyser, MikeKim,

Naomi Bowler,

Pranshu Gaba,

Rachel Bentley, Raymond Arndorfer, Rick Simineo, Roni, Rosie Paterson,

Sam Hartburn, Scott, Sheby, Shivanshi, Stephen Cappella, Steve Paget,

Thomas Smith, Tony Mann,

Valentin Vălciu, Yasha Ayyari, Zack Wolske, and Zoe Griffiths, who all also submitted the correct answer but were too unlucky to win prizes

this time.

See you all next December, when the Advent calendar will return.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2018-12-23

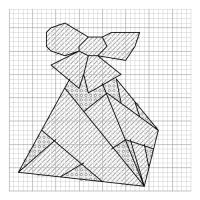

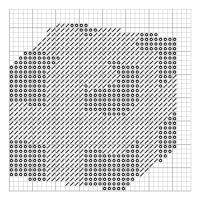

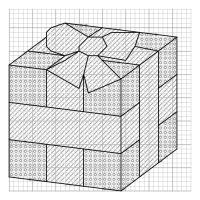

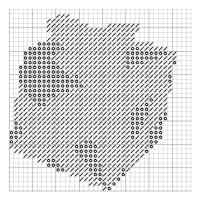

Recently, I made myself a new Christmas decoration:

Loyal readers may recognise the Platonic solid presents from last year's Christmas card, last year's

Advent calendar medals, or this year's Advent calendar medals.

If you'd like to make your own Platonic solids Christmas cross stitch, you can find the instructions below. I'm also currently putting together

some prototype Platonic solids cross stitch kits (that may be available to buy at some point in the future),

and will be adding these to the piles of prizes for this year's Advent calendar.

You will need

- A cross stitch needle

- Red cross stitch thread (for the ribbon)

- Black cross stitch thread (for the outlines)

- Non-red cross stitch thread (for the wrapping paper: I chose a different colour for each solid)

- Cross stitch aida

Instructions

Cross stitch thread is made up of 6 strands twisted together. When doing your cross stitch, it's best to use two strands at a time:

so start by cutting a sensible length of thread and splitting this into pairs of strands. Thread one pair of strands into the needle.

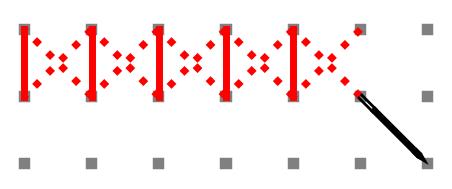

Following the patterns below, cross stitch rows of red and non-red crosses. To stitch a row, first go along the row sewing diagonals in one direction,

then go back along the row sewing the other diagonals. When you've finished the row, move the the row above and repeat. This is shown in the

animation below.

When doing the first row, make sure the stiches on the back cover the loose end of thread to hold it in place. Looking at the back of the

aida, it should look something like this:

When you are running out of thread, or you have finished a colour, finish a stitch so the needle is at the back.

Then pass the needle through some of the stitches on the back so that the loose end will be held in place.

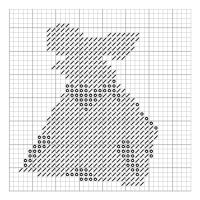

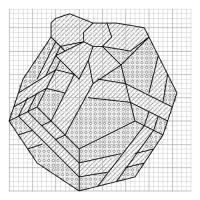

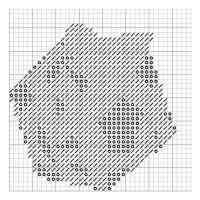

The patterns for each solid are shown below. For each shape, the left pattern shows which colours you should cross in each square

(/ means red, o means non-red); and the right pattern shows where to add black lines after the crosses are all done.

Pattern for a tetrahedron (click to enlarge)

Pattern for a cube (click to enlarge)

Pattern for a octahedron (click to enlarge)

Pattern for a dodecahedron (click to enlarge)

Pattern for a icosahedron (click to enlarge)

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment

2018-12-16

By now, you've probably noticed that I like teaching matchboxes to play noughts and crosses.

Thanks to comments on Hacker News, I discovered that I'm not the only one:

MENACE has appeared in, or inspired, a few works of fiction.

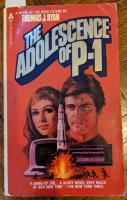

The Adolescence of P-1

The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1] is the story of Gregory Burgess, a computer programmer who writes a computer program that becomes sentient.

P-1, the program in question, then gets a bit murdery as it tries to prevent humans from deactivating it.

The first hint of MENACE in this book comes early on, in chapter 2, when Gregory's friend Mike says to him:

"Because I'm a veritable fount of information. From me you could learn such wonders as the gestation period of an elephant or how to teach a matchbox to win at tic-tac-toe."Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], page 27

A few years later, in chapter 4, Gregory is talking to Mike again. Gregory asks:

"... How do you teach a matchbox to play tic-tac toe?""What?""You heard me. I remember you once said you could teach a matchbox. How?""Jesus Christ! Let me think . . . Yeah . . . I remember now. That was an article in Scientific American quite a few years ago. It was a couple of years old when I mentioned it to you, I think.""How does it work?""Pretty good. Same principal of reward and punishment you use to teach a dog tricks, as I remember. Actually, you get several matchboxes. One for each possible move you might make in a game of tic-tac-toe. You label them appropriately, then you put an equal number of two different coloured beads in each box. The beads correspond to each yes/no decision you can make in a game. When a situation is reached, you grab the box for the move, shake it up, and grab a bead out of it. The bead indicates the move. You make a record of that box and color, and then make the opposing move yourself. You move against the boxes. If the boxes lose the game, you subtract a bead of the color you used from each of the boxes you used. If they win, you add a bead of the appropriate color to the boxes you used. The boxes lose quite a few games, theoretically, and after the bad moves start getting eliminated or statistically reduced to inoperative levels, they start to win. Then they never lose. Something like that. Check Scientific American about four years ago. How is this going to help you?"Taken from The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan [1], pages 41-42

The article in Scientific American that they're talking about is obviously A matchbox game learning-machine by Martin Gardner [2].

Mike, unfortunately, hasn't quite remembered perfectly how MENACE works: rather than having two colours in each box for yes and no, each box actually has a different colour for each possible move that could be made next.

But to be fair to Mike, he read the article around two years before this conversation so this error is forgivable.

In any case, this error didn't hold Gregory back, as he quickly proceeded to write a program, called P-1 inspired by MENACE.

P-1 was first intended to learn to connect to other computers through their phone connections and take control of their supervisor, but then

Gregory failed to close the code and it spent a few years learning everything it could before contacting Gregory, who was obviously a little

surprised to hear from it.

P-1 has also learnt to fear, and is scared of being deactiviated. With Gregory's help, P-1 moves much of itself to a more secure location.

Without telling Gregory, P-1 also attempts to get control of America's nuclear weapons to obtain its own nuclear deterrent, and starts

using its control over computer systems across America to kill anyone that threatens it.

Apart from a few Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award worthy segments,

The Adolescence of P-1 is an enjoyable read.

Hide and Seek (1984)

In 1984, The Adolescence of P-1 was made into a Canadian TV film called Hide and Seek [3].

It doesn't seem to have made it to DVD, but luckily the whole film is on

YouTube.

About 24 minutes into the film, Gregory explains to Jessica how he made P-1:

Gregory: First you end up with random patterns like this. Now there are certain rules: if a cell has one or two neighbours, it reproduces into the next generation. If it has no neighbours, it dies of loneliness. More than two it dies of overcrowding. Press the return key.Jessica: Okay. [pause] And this is how you created P-1?Gregory: Well, basically. I started to change the rules and then I noticed that the patterns looked like computer instructions. So I entered them as a program and it worked.Hide and Seek [3] (1984)

This is a description of a cellular automaton similar to Game of Life, and not a great way to make a machine that learns.

I guess the film's writers have worse memories than Gregory's friend Mike.

In fact, apart from the character names and the murderous machine, the plots of The Adolescence of P-1 and Hide and Seek don't have much in common.

Hide and Seek does, however, have a lot of plot elements in common with WarGames [4].

WarGames (1983)

In 1983, the film WarGames was released. It is the story of David, a hacker that tries to hack into a video game company's computer, but accidentally

hacks into the US governments computer and starts a game of Global thermonuclear war. At least David thinks it's a game, but actually

the computer has other ideas, and does everything in its power to actually start a nuclear war.

During David's quests to find out more about the computer and prevent nuclear war, he learns about its creator, Stephen Falken.

He describes him to his girlfriend, Jennifer:

David: He was into games as well as computers. He designed them so that they could play checkers or poker. Chess.Jennifer: What's so great about that? Everybody's doing that now.David: Oh, no, no. What he did was great! He designed his computer so it could learn from its own mistakes. So they'd be better they next time they played. The system actually learned how to learn. It could teach itself.WarGames [4] (1983)

Although David doesn't explain how the computer learns, he at least states that it does learn, which is more than Gregory managed in Hide and Seek.

David's research into Stephen Falken included finding an article called Falken's maze: Teaching a machine to learn in

June 1963's issue of Scientific American. This article and Stephen Falken are fictional, but perhaps its appearance in Scientific American

is a subtle nod to Martin Gardner and A matchbox game learning-machine.

WarGames was a successful film: it was generally liked by viewers and nominated for three Academy Awards. It seems likely that the creators of

Hide and Seek were really trying to make their own version of WarGames, rather than an accurate apatation of The Adolescence of P-1. This perhaps explains the similarities

between the plots of the two films.

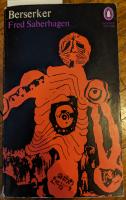

Without a Thought

Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5] is a short story published in 1963. It appears in a collection of related short stories by Fred Saberhagen called Bezerker.

In the story, Del and his aiyan (a pet a bit like a more intelligent dog; imagine a cross between R2-D2 and Timber) called Newton are in a spaceship fighting against a bezerker. The bezerker has

a mind weapon that pauses all intelligent thought, both human and machine. The weapon has no effect

on Newton as Newton's thought is non-intelligent.

The bezerker challenges Del to a simplified checker game, and says that if Del can play the game while the mind weapon is active, then he

will stop fighting.

After winning the battle, Del explains to his commander how he did it:

But the Commander was watching Del: "You got Newt to play by the following diagrams, I see that. But how could he learn the game?"Del grinned. "He couldn't, but his toys could. Now wait before you slug me" He called the aiyan to him and took a small box from the animal's hand. The box rattled faintly as he held it up. On the cover was pasted a diagram of on possible position in the simplified checker game, with a different-coloured arrow indicating each possible move of Del's pieces.It took a couple of hundred of these boxes," said Del. "This one was in the group that Newt examined for the fourth move. When he found a box with a diagram matching the position on the board, he picked the box up, pulled out one of these beads from inside, without looking – that was the hardest part to teach him in a hurry, by the way," said Del, demonstrating. "Ah, this one's blue. That means, make the move indicated on the cover by the blue arrow. Now the orange arrow leads to a poor position, see?" Del shook all the beads out of the box into his hand. "No orange beads left; there were six of each colour when we started. But every time Newton drew a bead, he had orders to leave it out of the box until the game was over. Then, if the scoreboard indicated a loss for our side, he went back and threw away all the beads he had used. All the bad moves were gradually eliminated. In a few hours, Newt and his boxes learned to play the game perfectly."Taken from Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen [5]

It's a good thing the checkers game was simplified, as otherwise the number of boxes needed to play would be

way too big.

Overall, Without a Thought is a good short story containing an actually correctly explained machine learning algorithm. Good job Fred Saberhagen!

References

[1] The Adolescence of P-1 by Thomas J Ryan. 1977.

[4] WarGames. 1993.

[5] Without a Thought by Fred Saberhagen. 1963.

(Click on one of these icons to react to this blog post)

You might also enjoy...

Comments

Comments in green were written by me. Comments in blue were not written by me.

Add a Comment